HOUSECAT NATION

Don't be neutered by modern life.

We are a nation of housecats. Most people in developed countries sit on their keisters all day at their jobs, and then go home and park it in front of a screen. 97 percent of our time is spent indoors. It’s not good for you, and pedaling on a bike to nowhere for an hour isn’t going to make up for ten or twelve hours sitting on your caboose. It’s far more effective to integrate movement throughout the day instead. Take a fifteen-minute break and walk around the block—you’ll come back refreshed and more productive, too. Sir J.A. Muir Gray, a leading public health advocate in the UK, believes that Type 2 diabetes should be renamed “walking deficiency syndrome,” because the disease can be a result of our sedentary lifestyles and modern environment.

People who do moderate exercise such as walking (or golf, swimming, or dancing) describe feeling more energetic, more socially connected, and more emotionally balanced. They also report decreased pain and diminished depression. Walking reduces stress, blood pressure, and body fat. Just carrying around extra body fat can impact pain symptoms; even an additional five to ten pounds can increase the stress on your knee and hip joints. Weight management and incorporating any exercise plan are often overlooked complements to pain management. Walking also improves quality of sleep, strengthens the heart, and increases muscle and bone strength. Unlike a stationary bicycle or a treadmill, it takes you places. Hey, you might even find some money on the street!

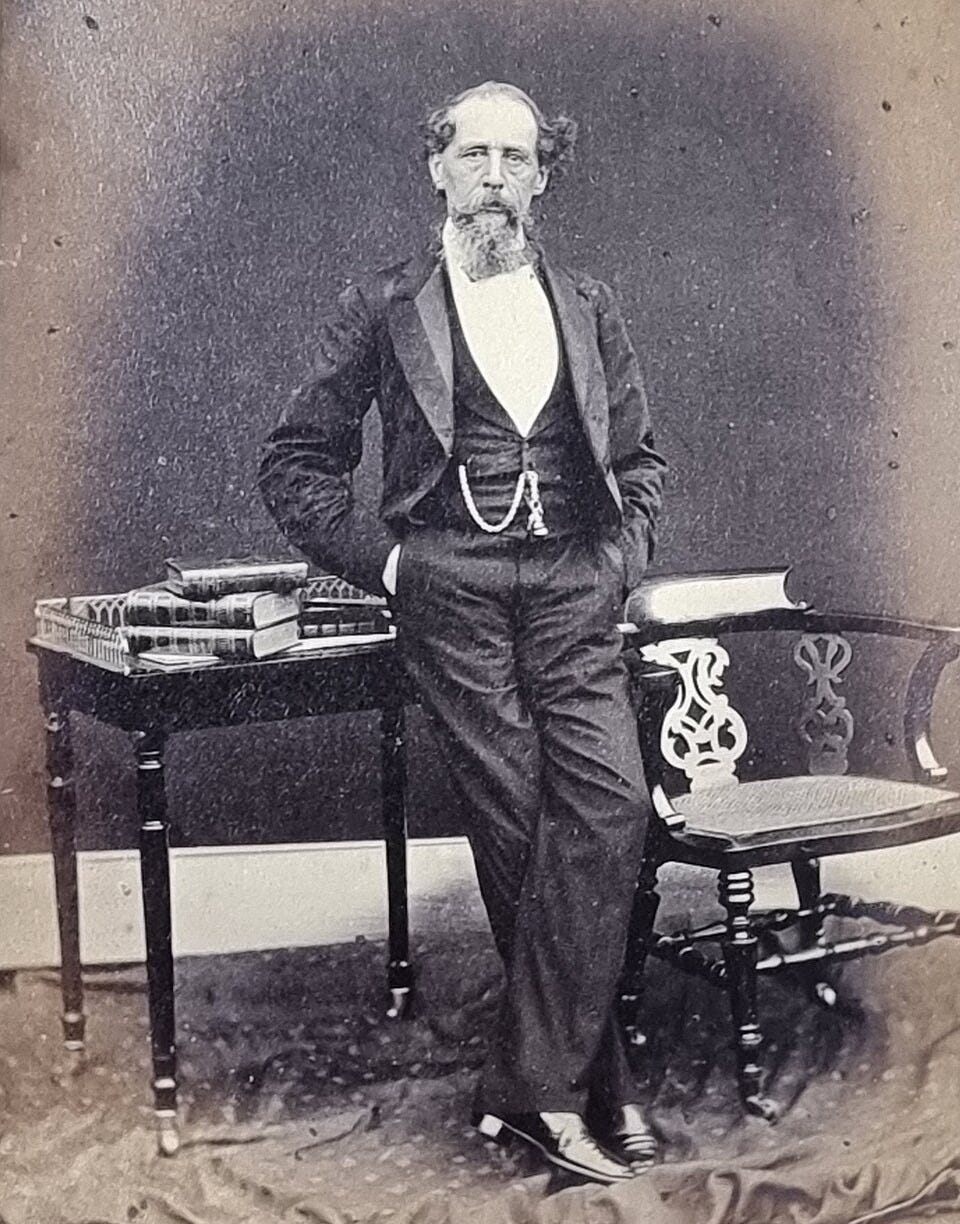

The benefits of walking aren’t exactly news, either. Over two hundred years ago, Thomas Jefferson not only informed us that we had been endowed by our creator with the rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, he urged us out of the house with these words: “Walking is the best possible exercise. Habituate yourself to walk very far.” And Charles Dickens, who was not really paid by the word but wrote as if he were, said, “The sum of the whole is this; walk to be happy; walk to be healthy. The best way to lengthen our days is to walk steadily and with a purpose. The wandering man knows of certain ancients, far gone in years, who have staved off infirmities and dissolution by earnest walking—hale fellows, close up on ninety, but brisk as boys.”

Well, you want to be brisk as a boy at ninety, don’t you? I do, and I’m a woman.

I find that the pedometer in my smart watch helps get me going. It’s incredibly satisfying to look and see the number of steps going up, up, up. Counting steps can be addictive, and by setting goals you’ll find yourself increasing movement in your daily life. Ten thousand steps a day is a common target, though that’s for an able-bodied person; your goal may be different. My family is competitive, and we all have pedometers, so if I don’t make my personal goal by the end of the day, I’ll march around my apartment in my knickers, pacing like a Silverback Gorilla until I hit my target number. My husband says bouncing my knees while I’m sitting on my butt drinking a glass of wine doesn’t count, but my smart watch doesn’t know that.

One related health tip I can share is to not wear a candy bracelet on the same wrist as your smart watch. You can crack a tooth if you latch on to the wrong item.

Walking is not just a physical exercise; it’s a metaphysical exercise as well. There’s a transformative power in perambulation. Walking engages not only our bodies but also our minds. As Friedrich Nietzsche wrote, “All truly great things are conceived by walking.” “Flaneur” is the French word for walker, or saunterer. A flaneur is someone who walks as a mode of self-expression and exploration. For the flaneur, walking is not about getting from point A to point B, or about getting in shape. The act of walking is its own reward. A flaneur walks the city in order to experience it, to fully participate through observation and peregrination.

The original flaneurs were literary types in nineteenth-century Paris. They were connoisseurs of the streets. Poet Charles Baudelaire, a noted flaneur, called himself a “botanist of the sidewalk.” Flaneurs transformed what was mindless transit into mindful exploration. They walked to become calmer, more insightful and meditative, in the belief that the quality of thoughts that erupt during walks are superior to less ambulatory thinking. Flaneurs would sometimes walk a pet turtle or lobster on a leash, just to enforce a leisurely, contemplative pace.

Medical researchers report that walking stimulates the brain and enhances creativity because the rhythmic circumambulation reflects the cadence of our thoughts. Every step propels us through space, but also propels our thoughts. The visual stimulus of the panorama unfolding before us introduces new inspiration and creates new ideas. Walking provides an opportunity to process the day; it is a form of contemplation. It engages and connects you with your environment, and though you may walk alone, you are not lonely. Honoré de Balzac wrote that flaneurie, the act of flaneuring, is “the gastronomy of the eyes.” Each step satisfies our hunger for experience and knowledge.

In walking, Baudelaire said, “The flaneur is capable of finding a remedy for the ever-threatening ennui.”

Some of the greatest minds in history were flaneurs. Beethoven composed music in his head during his daily walks. Aristotle’s school of thought was named the Peripatetic school, because he believed that philosophical ideas were best explored “in peripateu”—while strolling about. Einstein, Darwin, Tchaikovsky, Thoreau, Dickens, Whitman, Goethe, and Steve Jobs all enjoyed their mind-expanding daily constitutionals (though not at the same time).

A flaneur is always a man, but only because a woman is called a flaneuse. The American transcendentalist and feminist Margaret Fuller was a flaneuse, a deep thinker and long walker, often in the company of her transcendentalist friends Emerson and Thoreau. Novelist Frances Trollope was a flaneuse, as was her French contemporary George Sand.

I was immediately drawn to the idea of a leisurely stroll around the city, because as much as I love walking around town, I’m never going to take the gold medal in speed walking. I find flaneurie an effective remedy for my chronic pain, and, so far, it has kept the ever-threatening ennui at bay. I enjoy the fertile solitude of an evening walk. My neurologist says that walking is actually a self-medicating behavior, because repetitive motions such as walking can have the same effect on the brain as meditation. Walking can calm the mind, distract it from chronic pain, steer it away from intrusive or destructive thoughts.

Exercise such as walking is believed to be as effective as anti-depressants in elevating your mood. So begin a walking routine for your heart and your head. Your new career as a flaneur will unlock the capacity to positively change other habits for the better. Make your motto “solvitur ambulando,” which in Latin means “It is solved by walking.”

Great article! Yes, there are many benefits to walking besides the obvious physical health benefits. I walk every day, sometimes multiple times depending how I feel. It always makes be feel better in both body and mind!