LOVE THE LIVING OF YOUR LIFE

You only get one, so why not?

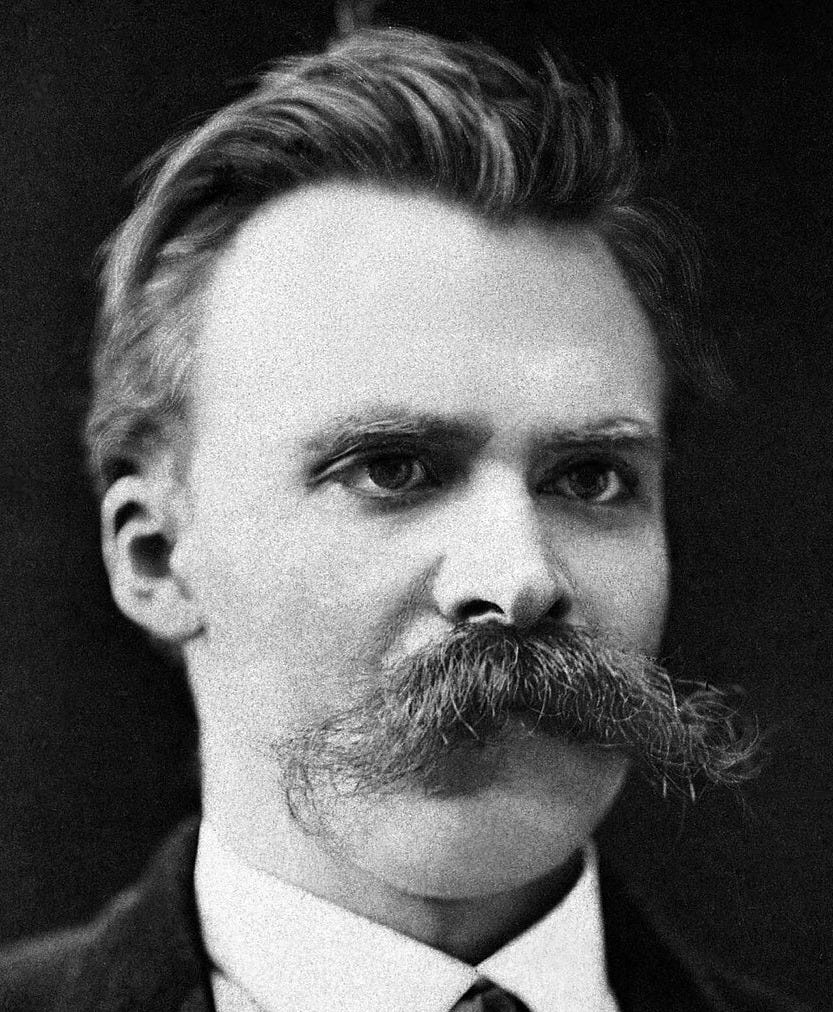

The idea of “amor fati,” a love of fate, is often associated with Stoicism. Yet this exact formula is found nowhere in the ancient Stoics. As a Latin phrase, it’s not from Marcus Aurelius, who wrote in Greek, or Epictetus, who lectured his students in Greek. Musonius Rufus, though Roman, lectured in Greek too. Seneca wrote in Latin, but these exact words don’t appear in his writings. In fact the phrase seems to have been popularized by Friedric Nietzsche, who was most decidedly not a Stoic.

Yet what idea could be closer to the heart of Stoic beliefs than amor fati? Like Seneca, we should not be afraid to borrow good ideas or mottoes from other schools of thought. Epictetus advises us, “Do not seek for things to happen the way you want them to; rather wish that what happens happens the way it happens, then you will be happy.” Isn’t this telling us to love our fate?

Our Stoic embrace of amor fati doesn’t mean we simply give in to whatever befalls us. We don’t huddle in a corner, cowering from life’s every vicissitude. Amor fati for we Stoics has two components: First, we take life as it is, not as we would wish it to be. Second, we take action based on our principles and the situation at hand. Amor fati is the opposite of passivity, it is a clear-eyed view of ourselves and our possibilities.

I practice amor fati every day. I live with a degenerative neurological condition and complex regional pain syndrome. These conditions do not have a cure, but they do have treatments that help tamp down the most painful episodes. I have accepted that this is my life, and Stoic wisdom has taught me that if I hated and fought my conditions, I would hate and fight every day. The Stoics, both Ancient and Modern, have taught me that you can’t control what happens; you can only control your response. Focusing on what I can control is the first step to building grit and mental strength.

Amor fati isn’t just about facing difficulty. It’s about embracing possibility. When I was at a low point in my life, dealing with severe illness, in a relationship that was falling apart, I met John Lambros. I jumped through the window that life had opened and instead of falling, I flew. We eloped five weeks later and thirty years later I still amor that fati.

“There surely exists a medicine for the soul,” Cicero wrote in his Tusculan Disputations. “It is philosophy.” People often turn to philosophy during times of grief and calamity. Discovering Epictetus, Marcus Aurelius, Seneca, and the whole roster of Stoics changed my life. Their clear, practical, and profound ideas expanded my view of life and rocketed me toward a sense of purpose, gratitude, and service. The Stoics illuminated the understanding that pain, loss, and distress are opportunities for growth and insight to love my fate. The vivid clarity of Stoic wisdom is as clear as the top line of an eye examination chart. Reading the Stoics was like trying on prescription lenses for the first time, unaware that I had been viewing the world through an astigmatism.

Every moment of our lives is an opportunity to practice amor fati. Good times are a chance to celebrate, the humdrum is a chance to seek out some razzmatazz, and bad times are an opportunity to bravely face adversity. The great classical historian Bettany Hughes once remarked, “Philosophy isn’t just about living our lives, it’s about loving the living of our lives.” To me, that is the highest refinement of the Stoic notion of amor fati. I love it all.

Great article! Very well said and so very true!! Amor fati!!!