THE ECCEDENTESIAST

You gotta laugh to keep from crying.

There is pain that hurts you and pain that changes you. Acute physical pain is a signal and a survival mechanism. In the short term it compels you to do something to avoid or diminish it—pull your hand away from the hot stove, jump back from a prickly cactus. Acute pain is usually caused by tissue damage and will resolve over a period of less than three months. It hurts, but it will go away. You’ll get better. You’ll go back to being the person you were before.

When your condition progresses from acute to chronic and the pain becomes permanent, this is the pain that changes you. There is physical pain, but there may be no visible injury. It’s inside, in the nervous system. It is invisible. The nerves never stop firing, sending constant pain signals to your brain. You can’t jump back from this pain. It follows you, and you have no choice but to reach an accommodation with it. You can medically dull it or mentally distract yourself from it, but you cancnever escape chronic pain.

The International Association for the Study of Pain has proposed this definition for pain: “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience, associated with actual or potential tissue damage." There is a major emotional component to dealing with chronic pain, but right now I’m just talking about the physical aspect.

The pain I endure is called neuropathic pain, which means it’s caused by damage to the nerves themselves, not to the surrounding tissue. According to the editor of PAIN, the Journal of the International Association for the Study of Pain, neuropathic pain is the most excruciating pain of all. I could have told him that myself and saved him the money he spent on his PhD.

The English word “pain” is rooted in the Latin “poena,” meaning “punishment” and “penalty,” as well as the sensation one feels when hurt. Chronic pain is like serving a life sentence. It’s punishment for a crime you didn’t commit.

One of the punitive effects of pain is that it is unshareable—it is difficult or impossible to express. To the sufferer, the pain cannot be denied. To the person next to her, the pain cannot be confirmed. Pain is subjective. It is unknowable unless you are afflicted with it. We tend to deny the pain of others because we can’t see it or feel it. It’s mystifying to us, unreal and frightening. We don’t want it to be true because we all fear being in pain. Pain means illness. Illness means limits and loss of freedom. If we admit someone else’s suffering, we admit the possibility that we might suffer too. And yet one-third of Americans have some type of chronic pain. That’s over 115 million people more than the number of people who suffer from heart disease and diabetes combined. So why is it so hard for us to talk about pain?

In The Body in Pain, Harvard professor Elaine Scarry writes that “physical pain does not simply resist language, but actively destroys it.” She studied the effects of severe and prolonged pain and noted that “pain is resistant to lingual expression, and this is part of the isolation that pain sufferers endure. A person in pain is bereft of the resource of language. She cites Virginia Woolf, who wrote, “English, which can express the thoughts of Hamlet and the tragedy of Lear, has no words for the shiver and the headache . . . the merest schoolgirl, when she falls in love, has Shakespeare or Keats to speak her mind for her; but let a sufferer try to describe a pain in his head to a doctor and language at once runs dry.”

Pain can reduce language, and the difficulty in describing it can compound the loneliness of a chronic condition. Because pain is so difficult to express, doctors at McGill University in Canada have created a questionnaire to help describe the severity of pain. It is seventy-eight questions long, and on the basis of your answers, it gives you seven words to describe the pain to your doctor. This is useful when you need medical help. But it’s not so helpful when answering the everyday question from a friend, “How are you feeling?”

Physical pain is isolating. Its inexpressibility and incomprehensibility separates you from your family and friends. My husband and son have no idea what it is like to live with chronic pain. They’re loving, funny, and compassionate, and they are essentially healthy. They, like most people, have a narrow frame of reference for how to comprehend pain. Their sprains and stitches and dental visits are finite, a sprint through pain. My chronic pain is an unending marathon of physical distress.

They can’t see the agony of the evil parrot perched on my shoulder, digging his sharp scaly claws into my shoulder and pecking my head and neck with its razor-blade beak. The torment that bursts in my neck and ruptures through my central nervous system is invisible.

From the moment I wake, before I even open my eyes, the pain detonates on the right side of my head, from the top of my ear through to my neck and shoulder. Then it jumps down my spinal column and over to my left elbow, igniting a searing, burning sensation that makes my left hand contract into a sad claw, a collapsed fist of fingers. Then the intense nerve jangling vibrates down my spinal column to my feet, where both my big toes feel like they have been snapped into a pair of rat traps. I’m amazed that my guys cannot see the raw pain in my body. How is it not visible? How can it not radiate out of me like the little jagged lines and stars emanating from an injured cartoon character?

The toughest part of my day is waking in the morning, arising with pain, swallowing, and then waiting for the medicine to kick in. It’s like waking up with a hangover, but I didn’t have the fun of getting hammered the night before. When the pain is at its worst, my head is tilted to the right like a broken Pez dispenser. I cannot tolerate the lightest touch; even wind will sting my neck.

When air hurts it is termed allodynia, meaning a painful reaction caused by a stimulus that would not normally cause pain. Sensations from showering, wearing a collared shirt, having hair strands brush against my neck, or even a light breeze can cause allodynia. Most pain serves a purpose, to protect an injured area. Allodynia flares pain for no useful purpose.

I take prescription medications to tamp down the burning, biting sharp sensations. Before the medicine takes effect, it feels like a donkey wearing hockey skates is kicking me in the neck. After the medication, it feels like the jackass put skate guards on, but he’s still kicking.

My vocabulary at these times consists of “ouch,” “yeow,” and “UGH!” Using profanity actually has a demonstrated palliative effect, but I’m not much of a curser. Not long ago, I was heading out to the patio to put sausages on the grill. The neuropathy in my feet impairs my spatial awareness, and I stubbed my foot on an Adirondack chair so hard that I broke two bones in my left foot. (I also dropped all the sausages.)

My husband drove me to the hospital, and when the doctor reset the bone back into place, it was one of the most painful things I’d ever experienced. I couldn’t help screaming, but I didn’t want to swear because there was a little kid in the ER. The doctor told me afterwards I was yelling “Mahatma Gandhi! Mahatma Gandhi!”

Other than talking about my pain, there’s really no way for people to know I’m seriously ill. You’ll see my defensive stance, ready to avoid anything that might touch the hot zone. You will not see my affliction. The granulomas and lesions are knotted up my spinal cord and in my central nervous system. I have an invisible illness.

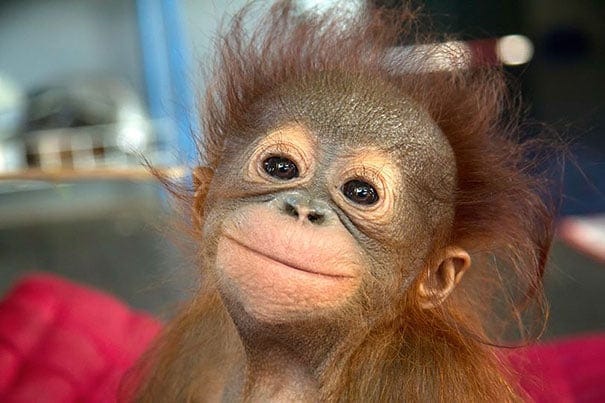

An eccedentesiast is someone who hides her misery behind a big fat smile, and that’s my approach to pain. I think it’s better than grimacing in agony, and there’s evidence that the act of smiling actually makes you happier. It’s frustrating that I can’t share my pain, but I’m trying to share my joy instead. As Lord Byron advised, “Always laugh when you can, it’s cheap medicine.”

Living with a degenerative disease is like living next door to a bully. You never know when he’s going to come over and ring your bell and knock you on your keister. Sarcoidosis is a part of me, and I am doing my best to peacefully cohabitate with it. I try to keep the pain-to-fun ratio leaning in my favor, and this is how I go on—smiling through the pain, trying to find a bright side. Every day I have a choice: to be useful or useless. I choose to be useful, or I try to, and this contributes to my happiness. I’ve had more than my share during my life. In a way, I think I am a very lucky unlucky person.

If you’re living with chronic pain, or know someone who is, I invite you to share your story in the comments. Also, September is Chronic Pain Month; don’t forget there are loads of resources available from the U.S Pain Foundation.

Somehow, you managed to just staple those sensations right onto my computer screen. I don't think I have been in the depths of pain that you describe, but everyone understands that feeling. Putting it in words is no small task. Good on ya, Duff and Francis!

Reaching out from the darkness - Mitch