THE STORK CLUB

Stork is a funny-sounding word, isn't it?

Storks live long lives. They can reach the age of seventy, and when they mate, they mate for life. Younger adult storks feed their elders and offer their extended wings as a crutch to enfeebled parents. Ancient Greeks called this loving care of the elderly “antipelargia.”

The Roman Senate was so impressed with this noble bird’s generous nature that it passed legislation titled Lex Ciconaria, or the Stork’s Law. This obligated adults to care for their elderly parents “in imitation of the stork.” I may not be quite up to the standard of storks, but I have been working with old folks since I was twelve.

I grew up in a conservative Roman Catholic family, and my parents expected their children to find a way to be useful in the world. I volunteered at the local nursing home and enjoyed the one-to-one contact and the challenge of connecting with another soul. In college, I got a degree as a recreational therapist. After graduation, my career and volunteer service was devoted to working with the elderly and disabled populations.

Over sixty-five million Americans care for a chronically ill, disabled, or elderly family member or friend. Nearly 30 percent of the population spends an average of twenty hours per week providing care for their seriously ill loved ones. One of the most difficult and emotionally complicated responsibilities you can take on is caring for an elderly relative.

This burden is largely unrecognized. In most cases, family caregivers are not financially compensated, and this enormous domestic work-force is overlooked and undervalued. The economic value of a family or friend caregiver is estimated to be over 600 billion dollars a year—which is nearly the entire annual budget for Medicare.

Many adults are struggling to raise kids while also caring for an ailing relative; they’re called the sandwich generation.The caregiving dynamic is even more complicated when the caregiver is living with a chronic illness of their own. It can feel like you’re being crushed by your responsibility to care for someone else while managing your own unpredictable illness.

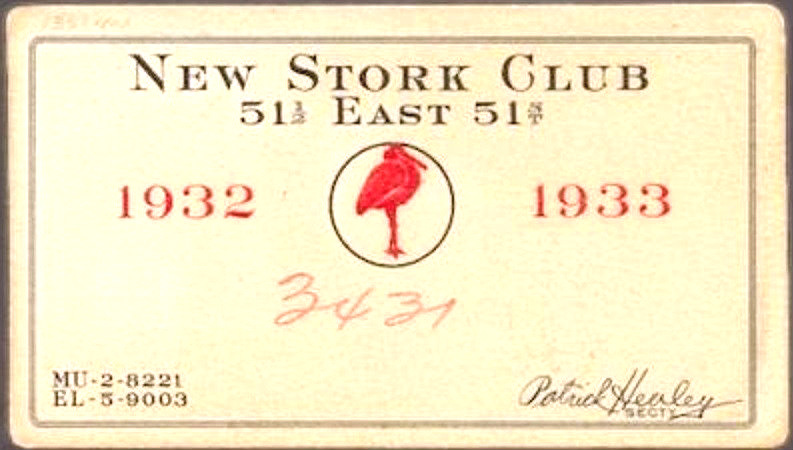

I understand the burden, because I’ve done it. People like me, with children, elderly relatives, and a chronic disease, are more like a triple-decker. We have an extra layer—we are the club sandwich generation. Call us members of the Stork Club.

Beyond the unrecognized monetary value of caregiving, the physical and emotional toll of extended domestic healthcare should not be underestimated. Family and friend caregivers are more susceptible to health issues of their own, such as depression, anxiety, and orthopedic injuries.

As the primary caregiver, we may be the only person our charge ever speaks to, the only person they see. We can become the receptacle for all their fears and frustrations, a punching bag for their anger. We are often required to perform medically complex tasks that are frightening for both the patient and caregiver. We clean, bathe, cook, do laundry, and tend to their most intimate personal needs.

It can be crushing. Self-care for the caretaker is not selfish—it’s soul-saving. Hospitals and community centers offer support groups and services for caregivers, and it is desperately needed.

We can all expect that at some point we will either fall ill and need a caregiver, or we will become a caregiver for someone who’s ill or injured. We may be called to mother our mother, or become skillful in fathering our father. For fifteen years, my family faced the challenge of caring for my husband’s grandmother. My father in law died in an accident, and we inherited the responsibility of caring for his nonagenarian Greek-American mother, Athena.

I thought I had the skill set to deal with being one of the primary caretakers of a cranky, bereft old woman. I don’t think an entire mustering of storks would have been able to peck away at her hostility.Athena’s husband died at the age of 103, a year before the unexpected death of her only child. The double blow did not blunt her sharp tongue. Sadness and misery were her whetstones, and every indignity, whether real or imagined, honed her ability to cut ever deeper.

When I worked at group homes, nursing homes, and hospice units, I would seek out the grouchy, smelly people. All the sweet old ladies in pink cardigans and blue-tinted curls got the smiles from the staff. I thought the grumpy ones could use the attention too. The difference was that I could leave the nursing home after my shift. But when you have a depressive, angry elder relative in your care, you can’t escape. You can’t walk away.

I had to develop an even thicker skin, selective deafness, and strategic mutism, and summon all my strength even when I had little to spare. Athena was family, and it was our duty to help care for her. We brought her groceries. We took her to the doctor, hair-dresser, and the department store. We’d take her to the family farm in Connecticut for the weekend. I’d call her the first thing in the morning and the last thing at night. We tried our best to help ease the pain of outliving her only child, but we didn’t make a dent in her depression.Once I was watching TV with her, and a commercial came on featuring a series of children declaring, “I was born to be an astronaut,” “I was born to be a fireman,” and so on. AndAthena, who was on the floor doing sit-ups, turned to me and said, “I was born to suffer.”

She was born (suffering, one presumes) in a rural Greek village. Yet she carried herself with all the vanity and snobbery of a grand dowager. She flaunted her razor-thin figure. Her speedy metabolism and her tiny waist were a source of eternal pride; she ate like a bird. She executed sets of crunches and marched in place. She was committed to her daily fitness regime. She viewed adipose tissue as a character flaw. I was still modeling, and when she saw me on the cover of a health and fitness magazine, her comment was “You aren’t really that big, are you?”

I could take it, but she gave her unsolicited opinion on Body Mass Index to her nurses, Bloomingdales’ sales associates, her infant great-grandson, and anyone ordering rice pudding in the neighborhood coffee shop. Athena taunted a visiting nurse about her weight so viciously that the poor woman was reduced to tears. The nurse left before the teakettle boiled.

Athena used her cane to nudge shop assistants to hurry them up. I’d double-tip any cab driver that ferried us around the city to compensate for her grousing and fussing. Andy Rooney once said, “The best classroom in the world is at the feet of an elderly person.” What I witnessed at the feet of this particular elderly person, besides bunions and hammertoes,was her iron will, her deep faith, and her unshakeable conviction that she was always right.

Athena was vital and bossy and unsentimental. She was surprisingly healthy for a wafer-thin centenarian. She had a pacemaker, and after ten years of service, the batteries needed to be replaced. We asked if the surgeon could just remove the pacemaker instead. It seemed to keep her kicking, and this was not a woman who was enjoying life. But the cardiologist said it didn’t work that way. The night before she was to get the new battery implanted in her ticker, I slept at her apartment. I had just interviewed the Rolling Stones for an HBO concert special. I made us Kahlua and milk cocktails, and we watched the program. She didn’t think my outfit did me any favors, and she helpfully pointed out that the camera adds at least ten pounds. She was fascinated that the Stones had an elderly Greek woman play-ing guitar. She was referring to Ron Wood.

Before we went to sleep, I told her I loved her and that tonight would be a great night to “go to the light.” I was right there in the twin bed next to her, so she need not be afraid. I would be with her and she could end her unhappiness. No neighbor would have to call and report an alarming smell coming from apartment 12P, and this was as good a time as any.

The next morning, she growled from her bed, “I’m still alive.”

In her late nineties, she was hit by a car while crossing the street. The only thing that broke was her cane. But she was infuriated that her crisp blue blazer was torn, and raged the entire way to the hospital about her jacket. In the emergency room, I had to fill out medical history and insurance forms. I asked her for her date of birth, and she barked that it was none of my business. I explained that I was not being nosy, but the hospital staff needed to know. “Well,” she sneered, “tell them they can ask my mother. She was there when I was born.” At that point her mother had been dead for at least eight decades.

Athena always excused her vagueness about her age by saying that in Greece all the records were destroyed in World War II. That would have been a valid excuse, except that she and her records had immigrated to the US in the 1920s, right after World War I.

When Athena was ninety-nine, she had a small stroke. Damage to the brain caused by a lack of blood flow is called a“stroke” because in the seventeenth century, it was believed the sufferer was actually “struck by the hand of God.” God didn’t hit Athena nearly as hard as He might have, but as Athena recovered in the hospital, we realized it was time for other measures. She could no longer live independently and terrorize shopkeepers, doormen, and anyone wearing stretch pants in public. She was nearly a century old, and we had to find an assisted living community.

The Greek Orthodox Home for the Aged rejected her for being too old. She hated the swanky Catholic nursing facility just a few blocks away from her Upper East Side apartment. She said it was intolerable because of all the Irish. Of course, I’m Irish Catholic.

We visited a succession of what former poet laureate Donald Hall called “old-folks storage bins” and “for-profit-making expiration dormitories.” We finally found a lovely location near our farm in Connecticut. But even though her venue had changed, Athena didn’t. Age had not mellowed her, infirmity did not calm her. Her snobbery and ill temper didn’t win her any popularity contests with the staff or the residents.

She chose to eat every meal alone. If I ever said hello to anyone in the dining room besides her, she’d shout insults at us across the room. The staff served ice cream and pie, and she served stink eye.

One December day, I dropped by so I could send out her Christmas cards. She was in a sour mood; she cranked up the grouchy to eleven for the holiday season. She asked what would happen if she stopped taking her medication. Her nurse said she would die. This answer seemed satisfactory, and from that moment on she refused to swallow her pills.

On New Year’s Eve, I stopped off at the liquor store and bought several airline-size bottles of Bailey’s Irish Cream and Kahlua. I had hoped we could have one last toast together, but by the time I got there, she was very weak and had her eyes closed.

I sat with Athena and told her she was loved and had nothing to fear. From working in nursing homes, I’d learned that hearing is the last sense to go. Don’t say anything you would not want your loved one to hear. Don’t fight over the jewelry or their gold teeth while they are still in the room.

Even though it was my last chance to let her have it, I talked about her faith instead.I took her hand to say goodbye. She opened her eyes and she seemed to perk up. It was like a sleeping tiger had been roused. She tried to bend my fingers backwards; I think she was trying to break them. When she wasn’t successful, she extended my middle digit so I was giving myself the finger. I’ll never forget her last words: “You stink on ice.”

She died that evening. The next morning, my son joined my husband and me in our living room as we made the funeral arrangements with the undertaker. He asked our son, “Would you like to write a letter or make a drawing for your great-grandmother?” Jack gently reminded him that she had died the night before and he didn’t think she would get the note.

The undertaker told us that in our village, in the Berkshire Mountains of northwest Connecticut, the snow and frozen ground made it impossible to bury anyone in the cemetery until the spring thaw. This was news to me. You can put a man on the moon in the cold of space, but you can’t put a ninety-pound woman six feet under when the temperature dips below freezing?

I asked where she’d be kept until she could be buried. He told me she would be in the basement of the funeral home in the deep freeze. I guess she was stinking on ice, too.

She was a very difficult woman, but I admired her for her toughness. I hope I’m as strong when I get to be her age. She wore hot-pink sequined high tops instead of orthopedic shoes. She was fearless and had driven an ambulance in World War II. She was sui generis, one of a kind.

I remember that once, near the end of her life, Athena told me that in her mind she was still a nineteen-year-old girl, coming to America to get married. In all the time I spent with her, it was the most beautiful thing she ever said. So that’s what I choose to remember of her, the hopeful young girl I never got a chance to meet in person.

In my dotage, rather than brimming over with bitterness, I will instead endeavor to model Seneca’s wise words: “We should cherish old age and enjoy it…Fruit tastes most delicious just when its season is ending.”

Great article! Very well done!

Absolutely charming. I've reread the Stranger recently. You've brought that back to mind.